A Love Letter to Historic Homes of Chicago’s Western Suburbs

My Childhood Home on West Jefferson Ave

Guys I’ll say it until I’m blue in the face—growing up in downtown Naperville is something I’ll forever be grateful for. I was extremely fortunate enough to live walking distance to my elementary, junior high, and high school, along with a single block from the riverfront, a three-minute walk to Centennial Beach, and was right on the cusp of downtown (the streets that still feel like home every time I walk them).

My parents actually still live in their home today— a beeeautiful Victorian-style property said to have been built in the early 1900s.

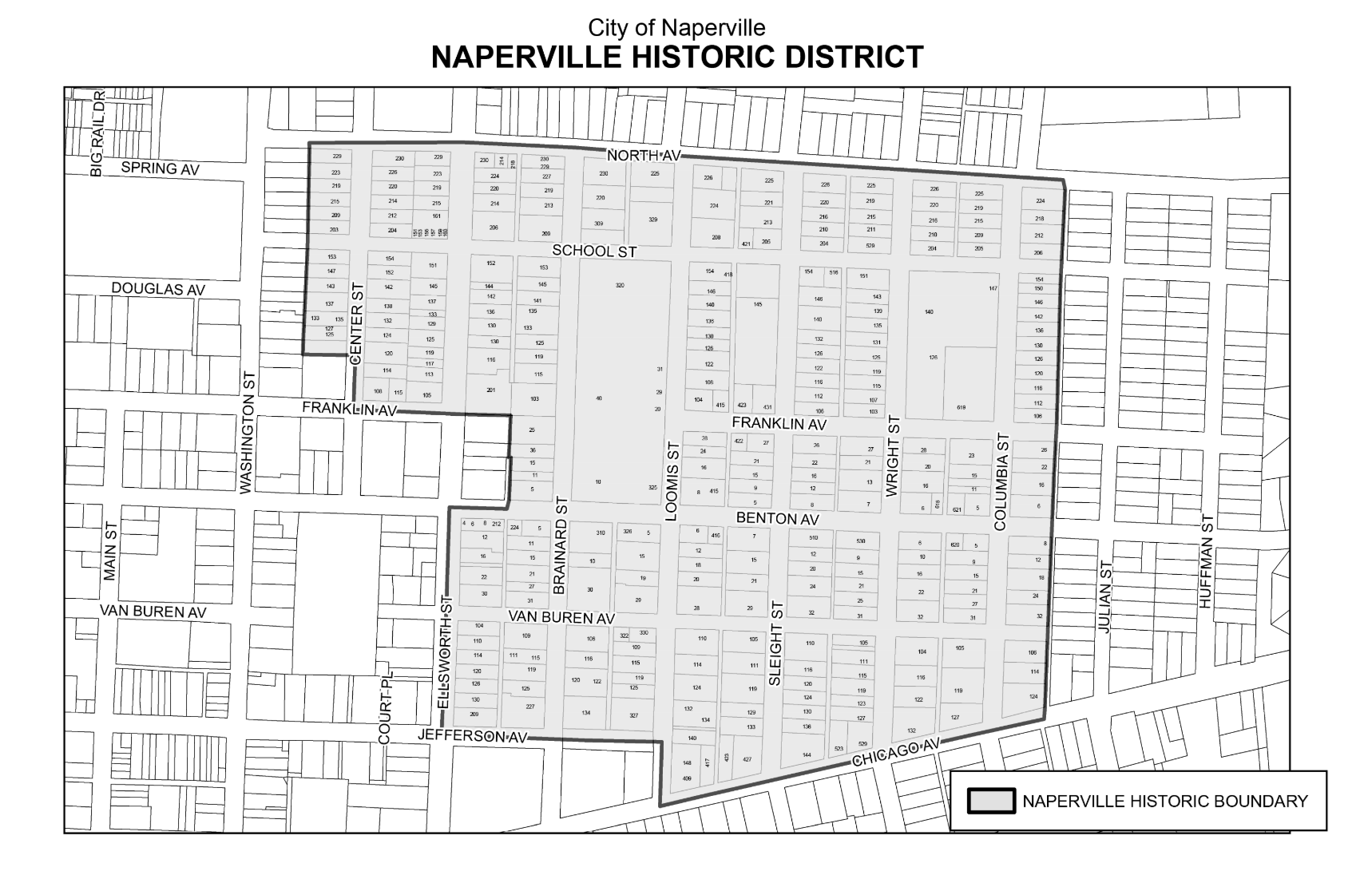

It’s not within the city’s Historic District (which is more near North Central College), but it’s still full of history & gorgeous character. Over the years my parents have done a few renovations—an addition to the back and some updates here and there—but the bones of their home have always remained.

My cute childhood home!

You almost can like feel its age, in the best way: like a house with endless stories to tell.

One thing I’ve always really appreciated about Naperville (and honestly, the same could be said about so many of the Western Suburbs) is the city’s genuine commitment to honoring and preserving history.

The lovingly maintained homes; an award-winning outdoor history museum: Naper Settlement (if you haven’t been, you absolutely have to go!); simply a walk through these neighborhoods where old trees tower over streets and wraparound porches. It’s clear that this is a town and community that doesn’t take its story for granted! And one of my favorite historical places to visit while on a walk through town is actually just a block away from my childhood home.

The Joseph and Almeda Naper Homestead

If you’re not familiar, Captain Joseph Naper is widely considered the “founding father” of Naperville. Along with his wife Almeda, he helped establish the early settlement that would eventually become the beautiful town we know today. In 2006, the City of Naperville purchased the homestead site (which is at the southeast corner of Jefferson Ave & Mill St) and turned it into a beautifully preserved, self-guided site—one that quietly honors Naperville’s roots in the very heart of town.

I just think there’s something so fascinating about this idea—the thought that these homes and places that we pass every day are holding history—deep, layered, living history. Some homes speak loudly through their architectural details: a mansard roof, hand-carved brackets, arched stained-glass windows. Others tell quieter stories through weathered siding or a crooked front step. And often, we don’t even realize we’re surrounded by these time capsules until we pause or really look.

The truth is, homes can be reflections of who we were and who we hoped to become—mirrors of politics, economics, industry, immigration, culture, craftsmanship, and care. Residential architecture is, quite literally, a physical imprint of our collective memory. And learning about it (even just a little) can give us a richer sense of place, and of knowing.

I want to be clear: this post isn’t meant to be a comprehensive encyclopedia of architectural styles, or of history. I’m writing a love letter to historical architecture, one of my all-time, forever favorite topics. If I’ve piqued your interest, below I will be spotlighting some of the most notable residential home styles found throughout the western suburbs of Chicagoland. These homes have stories, and they deserve to be seen in context (not just as aesthetic relics, but as part of broader, layered histories). For me, learning about & honoring history also means making space for the full picture (and not a polished, brochure version). History is multi-faceted. It holds beauty, yes—but also complexity, contradiction, and often, uncomfortable truths about how things, these towns, came to be. That’s something I believe is always worth remembering.

Before the Styles: Land, Displacement & Making of the Suburbs

Before there were neighborhoods. Before there were train lines. Before there were clapboard homes with sleeping porches and brick bungalows with wide eaves… the land that now makes up Chicago’s Western Suburbs held very different stories.

It’s really important that I begin by acknowledging that these communities exist because of forced displacement. Long before non-Native settlers arrived, the land now known as the Chicagoland area was home to Indigenous peoples and tribal nations—including the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, and Odawa, who together form the Council of Three Fires.

Other regional nations with deep ties to this land include the Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Miami, Sauk, and members of the Illinois Confederation. And for generations, these tribes lived across the Great Lakes region, overseeing land, water, and trade networks that predated any town plat or rail map.

In the 1830s, through a series of treaties (many of which were signed under coercion or manipulation), Indigenous peoples were forced to hand over their homelands. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 formalized a policy of displacement, and by the time settlers like Joseph Naper arrived in what would become Naperville, the Potawatomi were already being pushed west. This culminated in the Potawatomi Trail of Death in 1838, a forced march to Kansas that resulted in the deaths of many along the way.

My home is likely one of the oldest (if not the actual oldest) still-standing homes in DuPage County that is still residentially used, and it was originally constructed in the 1830s, possibly even earlier. Located in Glen Ellyn, my home (the George Baker House) is a nationally registered historic property (thanks to the tireless efforts of the previous owner, Marian). It was once part of a sprawling 300-acre farmstead, one of the earliest in the area. And its early history sits directly at the intersection of the events mentioned above.

In fact, the unincorporated land I live on today was first claimed by a non-Native settler family shortly after the Black Hawk War of 1832.

What I’ve learned is that this conflict began when a Sauk leader, Black Hawk, returned with his people to reclaim ancestral land that had been taken through a disputed and unjust treaty. Though his goal was to resettle peacefully, his return was met with hostility by non-Native settlers and the U.S. military. The response was violent and vastly disproportionate, leading to the deaths of many Indigenous people and ultimately enabling the widespread seizure and settlement of their lands across northern Illinois.

My property’s original deed dates back to this exact era. And when you live in a home with this kind of history already uncovered, at least for us, it forces you to think about land differently. This is something I feel grateful for. My home is not just an really neat old house with thick limestone walls and wood floors repurposed from an old school house. It tells a story and sits on land that carries a much older and more complicated one: one marked by removal, resistance & erasure. This awareness doesn’t take away from my love for the home itself, but it does add weight to how I think about it, and how I plan to live and exist through it. Just a little reminder that beauty and injustice can (and do) occupy the same ground—and that honoring one requires recognizing the other.

What followed across the region was non-Native settler expansion. Early housing in these newly claimed areas was largely utilitarian: log cabins, simple wood-frame dwellings, and vernacular homes built from local materials like timber, limestone, or brick. These structures were built primarily out of necessity (shaped by labor, geography, and the urgency of starting over). While many weren’t built with architectural style or long-term permanence in mind, some began to take on regional character and sturdier forms as communities grew.

As the mid-1800s progressed, towns like Naperville, Wheaton, Glen Ellyn, Oak Park, Riverside, and Hinsdale began to take more formal shape. The arrival of the railroad—Naperville’s station came in 1864—transformed the pace and scale of development. Suddenly, it became possible for people to live farther from Chicago while still maintaining access to the city for work and trade. That shift laid the groundwork for what we now understand as the “suburbs.”

In case you’re curious like I was, here’s a look of when many of these communities were founded:

Naperville – Settled: 1831 | Incorporated: 1857

Wheaton – Settled: 1830s | Incorporated: 1859

Glen Ellyn – Settled: 1834 | Incorporated: 1896

Oak Park – Settled: 1835 | Incorporated: 1902

Elmhurst – Settled: 1836 | Incorporated: 1882

Hinsdale – Settled: 1863 | Incorporated: 1873

Downers Grove – Settled: 1832 | Incorporated: 1873

La Grange – Settled: 1830 | Incorporated: 1879

Geneva – Settled: 1835 | Incorporated: 1867

Batavia – Settled: 1833 | Incorporated: 1872

There are of course plenty more places I could mention, but I can’t name them all here haha.

And before I shift into the architectural side of my post today, I want to say thank you for sticking with me through this part of my writing. The architectural beauty we admire today didn’t happen in a vacuum. It exists within a much longer history—one I believe we all have a responsibility to learn about and remember. This is why it feels important to also name what else shaped the growth of these communities: exclusion. Through policies such as redlining, racially restrictive covenants, exclusionary zoning, and more— many of the suburbs were intentionally structured to keep certain groups out (particularly Black families, immigrants, and low-income residents). Very ugly and horrible to imagine, yes. In the same decades when some of the area’s most beautiful homes were being built, discriminatory housing practices were also being enforced—through law, policy, and real estate.

So please please please remember these realities, because they undeniably shaped who had access to land, to ownership, to opportunity, and to the kind of stability that carries across generations. The impacts of these systems are still very much with us today. As someone working in the real estate industry, I take that responsibility seriously: to understand this history, to name it, and to not look away from it.

For Further Reading

Urban Institute – The Ghosts of Housing Discrimination Reach Beyond Redlining

NPR – A ‘Forgotten History’ Of How The U.S. Government Segregated America

History.com – How Neighborhoods Used Restrictive Housing Covenants to Block Nonwhite Families

NPR – Racial Covenants, A Relic Of The Past, Are Still On The Books Across The Country

University of Washington – Racial Restrictive Covenants Project

Investopedia – Single-Family Zoning: Definition, History, and Role in Racial Segregation

A Closer Look at the Notable Architectural Styles Found in the Western Suburbs

From modest two-flats to stately Victorians, the homes across the western suburbs reflect the eras they were built in—through their structure, materials, and architectural choices. Below I will highlight some of the most recognizable and historically significant residential styles found in towns like Naperville, Oak Park, Glen Ellyn, Wheaton, Hinsdale, Geneva, and many others nearby. Let’s start with a style that originated right here in the Chicago area.

Prairie Style (1890s–1920s)

Defined by: Horizontal lines, low-pitched or hipped roofs, overhanging eaves, Roman brick, art glass, open asymmetric plans, and integration with the landscape.

Emerging around the 1900’s, the Prairie Style was developed by a group of architects known as the Prairie School, led by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright. They believed that architecture should be rooted in its surroundings—not imposed on them. Drawing from the ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement and inspired by the wide, flat Midwestern landscape, they designed homes with strong horizontal lines, low-slung or hipped roofs, and wide, sheltering eaves that visually echoed the prairie horizon.

These homes were a clear break from the elaborate ornamentation of the Victorian era. Instead of turrets and trim, Prairie homes celebrated simplicity, structure, and craftsmanship. Interiors often featured open, asymmetrical floor plans, natural materials like stucco, wood, and brick, and beautifully integrated details—art glass windows, built-ins, and wood banding—all designed specifically for the home. Many also featured large central chimneys and connected indoor-outdoor spaces.

Though Prairie Style was relatively short-lived as a movement, its legacy is massive—especially here in the Chicago region. Oak Park, home to Wright’s own studio, holds the highest concentration of Prairie homes in the country. Nearby suburbs like Riverside (designed by Frederick Law Olmsted) became natural canvases for this architecture. Even outside of these hubs, it’s not uncommon to spot elements of Prairie design—like ribbon windows or cantilevered overhangs—in homes that blend styles or have been adapted over time.

And while the Prairie Style found its most iconic expression in residences, the philosophy extended to other buildings too (schools, park structures, even warehouses) where horizontal lines, stylized ornamentation, and rootedness in place guided the design.

Where to Find It: Oak Park, River Forest, Riverside, parts of Wheaton, Elmhurst, and scattered examples in Naperville and Glen Ellyn

Queen Anne / Victorian Style (1880–1910)

Defined by: Asymmetrical facades, steeply pitched roofs, turrets or towers, decorative gables, ornate trim (often called "gingerbread"), patterned shingles, and vibrant paint colors.

This is what my childhood home is! Of all the Victorian-era styles, Queen Anne is the most exuberant and instantly recognizable. These homes are romantic, highly decorative, and often a little eclectic—which makes sense, as the Queen Anne style was more of a catchall aesthetic than a rigid set of rules. If Prairie homes are restrained and horizontal, Queen Anne homes are their vertical, whimsical opposites.

Introduced in the U.S. in the late 1800s, this style gained popularity thanks to the expansion of railroads, which made it easier to ship decorative millwork and complex house plans across the country. That meant homeowners could now afford elaborate designs and prefabricated ornamentation, often ordered straight from a catalog.

Common features include asymmetrical layouts, wraparound porches, towers or turrets, textured wall surfaces (like fish-scale shingles), and a mix of materials and colors. No two are exactly the same, and that individuality is part of the charm. You’ll find these homes sprinkled throughout older parts of towns that saw growth in the late 19th century—particularly along main streets or in historic residential districts. In Naperville, for example, several stunning Queen Anne homes sit within walking distance of downtown and are often lovingly restored and maintained.

Despite their ornate appearance, these homes were more than just status symbols. They reflected a changing America—growing middle-class wealth, industrial innovation, and an increasing fascination with art, leisure, and domestic life.

Where to Find It: Naperville’s historic district, Geneva, Elgin, Wheaton, St. Charles, and parts of Hinsdale and Aurora

Craftsman / Arts & Crafts (1905–1930s)

Defined by: Low-pitched gabled roofs, wide eaves with exposed rafters, tapered porch columns, earthy materials like wood and stone, built-in cabinetry, and handcrafted details.

If the Queen Anne style was all about decorative excess, the Craftsman home was a deliberate return to simplicity, warmth, and honest craftsmanship.

Rooted in the Arts and Crafts movement—which began in Britain as a reaction against industrialization—the Craftsman style celebrated handmade work, natural materials, and design that felt grounded and livable. In the U.S., it took off in the early 1900s, spreading quickly through architectural magazines and popular home pattern books like those from Gustav Stickley or Sears, Roebuck & Co.

These homes often feature deep front porches, low-pitched roofs with exposed structural elements, and a strong sense of horizontality. Interiors were designed with just as much intention: built-in benches and bookcases, fireplaces with tile surrounds, and open layouts that prioritized family gathering over formal entertaining.

Craftsman homes come in all sizes—from small, bungalow-style homes to larger two-story versions—and their accessibility made them especially popular with middle-class homeowners. They were meant to be homes you could live in, not just look at.

Today, you’ll find beautiful examples across the western suburbs, especially in towns that grew steadily in the early 20th century. While many have been updated over time, the character-defining features—like tapered columns or wood detailing—still speak to their original spirit.

Where to Find It: Oak Park, La Grange, Elmhurst, Wheaton, Geneva, and scattered throughout Naperville and Glen Ellyn

American Foursquare (1890s–1930s)

Defined by: Boxy shape, two-and-a-half stories, four-room floor plan, front porch with wide stairs, hipped or pyramidal roof with central dormer.

Often referred to as the “workhorse” of early 20th-century American residential design, the American Foursquare is one of the most common (and beloved) historic home styles in the Midwest!

Born in a transitional period between Victorian ‘excess’ and modern ‘simplicity,’ the Foursquare offered a practical, no-nonsense alternative to its more ornamental predecessors. With its signature square shape and efficient four-room-per-floor layout, the style maximized usable space on modest lots. It was a perfect fit for the growing middle class and rapidly expanding suburban neighborhoods near streetcar lines and train stations.

Architecturally, the Foursquare is known for its hipped or pyramidal roof (sometimes with a front-facing dormer), full-width front porch, and minimal exterior ornamentation—though many were dressed up with touches from other styles, like Craftsman (e.g., exposed rafters, porch brackets) or Colonial Revival (e.g., classical columns, dentil molding). This adaptability made Foursquares both familiar and surprisingly diverse in their details.

Interior layouts typically followed a four-square room plan per level: living room, dining room, kitchen, and den downstairs; three or four bedrooms upstairs. Sturdy materials, built-ins, and quality millwork gave these homes lasting character, and many still stand proudly today.

You’ll find Foursquares scattered throughout the older neighborhoods of nearly every western suburb—especially those that saw major growth in the early 1900s. From Naperville to Elgin, their tall, boxy silhouettes and deep porches still anchor entire blocks. They weren’t flashy. But they were (and are) dependable, livable, and surprisingly elegant in their restraint.

Where to Find It: Naperville, Elgin, Aurora, Downers Grove, La Grange, Glen Ellyn, and just about every older neighborhood in the western suburbs

Colonial Revival (1880s–1950s)

Defined by: Symmetrical facades, central entry doors with pediments or columns, multi-pane double-hung windows (often with shutters), side-gabled or hipped roofs.

Colonial Revival homes were less about inventing new, and more about nostalgia. This style looked back—drawing direct inspiration from 18th-century Georgian and Federal architecture—but reinterpreted those forms for modern life in a growing, industrialized America. Think: Steve Martin’s house in Father of the Bride.

The movement first gained momentum after the 1876 U.S. Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, which sparked a nationwide interest in the country’s colonial roots. Architects and builders began reviving early American motifs: symmetrical facades, centered doorways framed by pilasters or fanlights, and classical elements like pediments, dentil molding, and sidelights.

Colonial Revival homes were often constructed of brick or wood, with restrained ornamentation and a sense of balance and order. Many had side-gabled or hipped roofs with dormers, and the front entry was almost always emphasized—framed by columns, a portico, or an elaborate door surround. Windows were typically double-hung with multiple panes, often arranged symmetrically across the facade, and shutters (whether functional or not) were common.

This style wasn’t just for large, formal homes. Its adaptability meant it appeared in modest cottages, stately two-stories, and even in brick apartment buildings and townhomes. It became one of the most dominant suburban styles through the mid-1900s and is still frequently emulated today.

In the western suburbs, Colonial Revivals can be found everywhere from the grand homes of Hinsdale and River Forest to the more modest streets of Wheaton and Naperville. Whether dressed up with decorative flair or kept crisp and simple, these homes reflected a deep desire for familiarity, tradition, and stability during a century of rapid change.

Where to Find It: Hinsdale, Wheaton, Naperville, Oak Park, La Grange, River Forest, and nearly every suburb developed during the early-to-mid 20th century

Italianate & Second Empire (1850s–1880s)

Defined by: (Italianate) Tall, narrow proportions, low-pitched or flat roofs, wide eaves with decorative brackets, arched windows, and cupolas or belvedere. (Second Empire) Mansard roofs with dormer windows, strong vertical emphasis, ornate detailing, often with similar brackets and moldings as Italianate homes.

Italianate and Second Empire styles emerged in the mid-19th century as part of a broader movement toward more romantic and expressive architecture. While they’re distinct styles, they often share similar details and are sometimes grouped together because of overlapping timelines and visual elements.

Italianate style drew inspiration from the rural villas of Italy and became wildly popular in the U.S. after the 1850s, especially as a symbol of affluence and cosmopolitan taste.

These homes were typically two to three stories tall, with low-pitched or even flat roofs, bracketed eaves, and tall windows—often rounded or arched. They frequently featured belvederes or cupolas and ornamental window hoods. Despite their European inspiration, Italianate homes were built using American balloon framing methods, which made their dramatic proportions easier to achieve.

Second Empire, by contrast, takes its name from the reign of Napoleon III in France and is best recognized by its mansard roof—a dual-pitched hipped roof with dormer windows popping out of the steep lower slope.

This design allowed for a full upper story of usable living space and quickly became a fashionable urban and suburban solution. Like Italianate homes, Second Empire houses often included elaborate moldings, bracketed cornices, and tall, narrow windows.

In the western suburbs, these styles tend to appear near original village cores or along early rail corridors—places like downtown Elgin, central Geneva, and historic Naperville, where early prosperity brought in architects and builders working in these high-style trends. While fewer in number than later styles, they’re unforgettable when you do find them: bold, vertical, and unmistakably 19th century.

Where to Find Them: Older parts of Naperville, Elgin, Geneva, and St. Charles; scattered examples in Wheaton and Oak Park; typically near original town centers or railroad-adjacent development

Georgian Revival & Minimal Traditional (1920s–1950s)

Defined by: (Georgian Revival) Symmetry, brick exteriors, paneled doors with decorative crowns, multi-pane windows, and classical detailing like columns or pilasters. (Minimal Traditional) Simplified traditional forms, minimal ornamentation, low-pitched gable roofs, small front porches or stoops, and compact footprints.

Georgian Revival, also known as Colonial Revival’s more formal sibling, emerged in the early 20th century as a nostalgic nod to 18th-century British and American architecture. These homes are rooted in symmetry and order, with central entrances often framed by pilasters or columns, side-gabled or hipped roofs, and multi-pane, double-hung windows. Brick is a defining material, giving these homes a solid, stately appearance. Inside, you’ll often find traditional floor plans with separate formal living and dining rooms—ideal for the conventions of the era.

As the 1930s gave way to the 1940s and beyond, the Minimal Traditional style began to take hold. These homes carried forward familiar traditional forms—like gabled roofs and simple rectangular massing—but stripped away most decorative flourishes.

They were practical, efficient, and modest in size, often built to meet the needs of middle-class families during and after the Great Depression and World War II. Unlike the grandeur of earlier revival styles, Minimal Traditional homes reflect the economic realities of the time, offering affordable comfort with just a touch of tradition.

You’ll often find both styles in the same neighborhoods: the Georgian Revival homes anchoring corners or slightly larger lots, while Minimal Traditional houses fill in the blocks around them, especially in areas developed in the 1940s and early 1950s. They offer a snapshot of America’s shifting priorities—formality and status giving way to practicality and accessibility.

Where to Find Them: Naperville, Hinsdale, Wheaton, Elmhurst, Glen Ellyn, and pockets of postwar development throughout the western suburbs

Cape Cod & Mid-Century Ranch (1930s–1960s)

Defined by: (Cape Cod) Steeply pitched roofs, central chimneys, symmetrical facades, dormer windows, and simple rectangular forms. (Ranch) Long, low, ground-hugging profiles; open floor plans; attached garages; large picture windows; and an emphasis on indoor-outdoor living.

Cape Cod homes trace their roots back to 17th-century New England, but they saw a major revival in the 1930s and ’40s, especially through mass developments like Levittown. In the Midwest, they became a staple of modest suburban neighborhoods—simple, boxy, and practical, with room to grow. These homes often feature a central front door flanked by windows, and dormers added for headroom when second floors were finished. Their cozy scale and symmetrical simplicity made them especially popular for returning WWII veterans and young families.

By the late 1940s and into the 1950s and ’60s, the Mid-Century Ranch emerged as a bold departure from the verticality and formality of earlier styles. Inspired by modernist principles and the postwar fascination with cars, technology, and space, Ranch homes sprawled across their lots with single-story layouts and easy access to outside. Sliding glass doors, integrated garages, and open-concept living spaces defined the look.

Unlike Cape Cods, Ranch homes celebrated asymmetry and flow, blurring the lines between inside and out.

These two styles often coexist in the same postwar neighborhoods—Cape Cods marking the earlier phases, Ranches arriving as tastes shifted toward informality, convenience, and the optimism of the atomic age. Both are emblematic of the American dream as it was reimagined in the 20th century: accessible, suburban, and rooted in a desire for privacy, space, and simplicity.

Where to Find Them: Naperville, Downers Grove, Lombard, Glen Ellyn, Western Springs, La Grange, and in many first-ring postwar neighborhoods

Post-War & Modern-Day Influence

After World War II, the American housing landscape changed dramatically—and so did the suburbs of Chicagoland. With returning veterans, federal loan programs, and a growing middle class, demand for single-family homes skyrocketed. In response, developers across the region turned to mass production and efficiency, ushering in an era of tract housing and a more modern suburban form.

The Rise of Tract Housing

Inspired by developments like Levittown on the East Coast, builders in the Midwest began producing neighborhoods at scale. Homes were smaller, simpler, and quickly built—often nearly identical, save for subtle variations in orientation or façade details. While not as architecturally expressive as earlier styles, these homes represented accessibility, stability, and the growing promise of post-war homeownership. You’ll see these pockets in towns like Lombard, Westmont, Villa Park, and areas of Naperville that were built up through the 1950s and early ’60s.

Ranch Homes

If there’s one home style that defines the mid-century suburbs, it’s the ranch. Low-slung, long, and often L- or U-shaped, ranch homes embraced open interior plans and a deep connection between indoor and outdoor living. Garages were attached, yards were expansive, and everything was oriented around the car. These homes were intentionally casual—no formal parlors or grand entries—designed for relaxed, functional, family life. Ranches remain widespread throughout DuPage and Kane counties, especially in neighborhoods that expanded between the 1950s and 1970s.

Split-Levels & Raised Ranches

To make even more efficient use of modest suburban lots, the split-level and raised ranch models became common. By stacking living areas—often with partial floors staggered across multiple levels—these homes packed bedrooms, living rooms, and recreation space into compact footprints. Their layouts also responded to changing family needs, separating quieter sleeping quarters from more active spaces like dens or lower-level family rooms. You’ll find these styles in abundance across towns like Downers Grove, Glen Ellyn, and the early post-war rings of Naperville.

Modernism & Brutalism—Yep, Even Here!

While less common in single-family homes, modernist and brutalist architecture found their way into public and civic buildings throughout the suburbs. Mid-century schools, libraries, post offices, and even churches experimented with concrete, minimal ornamentation, and bold, geometric forms. You can see hints of this in some older apartment buildings or municipal structures—often built during the same decades when suburban populations were booming and infrastructure needed to catch up.

Some Closing Thoughts

If there’s one thing I hope today’s post conveys, it’s that homes and places all over are shaped by: time, place, and as we learn more and more about: power. The architecture of the western suburbs tells a layered story. From limestone farmhouses (my qt house!) and early Victorian builds to Prairie masterpieces, mid-century ranches, and beyond, every style has something to say about the era it came from and the people it was built for. But just as important as what was built is who got to build, own, and keep it—and who didn’t.

This kind of awareness doesn’t just help us admire these homes more, it helps us understand them! It can sharpen the way we see craftsmanship, layout, renovation choices, and even resale potential. And that’s where I come in! If you’re interested in buying, selling, or just exploring real estate in the Chicagoland area— I’m here to help you read between the lines of a home, whether that means noticing what was added (or stripped away), thinking through what’s original versus worth reimagining, or guiding a decision with both strategy and intention. In a market this nuanced, care and context actually make all the difference.

So if this is the kind of support you’re looking for, I’d love to be a resource to you, anytime!

Stay happy and healthy,